Book Review: How To Film Moving Pictures in the 1910s

- Aug 24, 2018

- 2 min read

There is an area of film history that is not about aesthetics. The technology of shooting movies evolves so much and so quickly, we sometimes forget to realize that the effects in a Buster Keaton silent were done without CGI, and that painful pratfalls and dangerous heights were exactly as they seemed.

In his new book, “How To Film Moving Pictures in the 1910s,” author Darren Nemeth explores early filmmaking and presents, as a veritable book-length documentary, the results of his research verbatim so that we too can benefit from his findings. “How To Film Moving Pictures in the 1910s,” is a fascinating collection of reprinted booklets that explain the machines used to create the early filmmaking process.

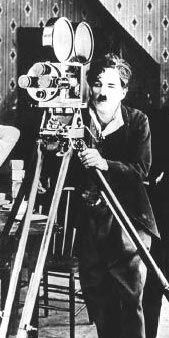

First we have to assess just how much filmmaking developed during cinema's earliest years. Narrative film was introduced at the turn of the century. Editing and cross-cutting was used to tell the story. Characters were defined by menacing close-ups. By 1914, Charlie Chaplin added depth to a screen character, making him both a comic and tragic figure. He co-starred in the first feature length comedy that year. The D.W. Griffith epic “Birth of a Nation” went into production. By the end of the 1910s, the motion picture industry was not only a booming business it was filled with creative achievement that only grew during the next decade.

The material Nemeth has chosen for this book are a fascinating collection of careful details explaining the rudiments of motion picture photography, the type of film used, the structural development of the mechanism, and the ability to create a succession of different shots. Manuals explain how to operate a wooden, hand-cranked camera, and how to process film. It gives us an intriguing glimpse into early filmmaking, its processes, and its experimentation.

The technical details are very intricate and it reminds one of the aforementioned Buster Keaton, who was so fascinated by the process on the set of his first film, “The Bucher Boy (1917), that he asked, and received, permission to bring a camera home so he could take it apart and see how it worked. He did, and put it back together. The resourceful Keaton realized that film’s technological process was indeed a factor in its aesthetic success.

Nemeth closes his book with several frame blowups of early silent films, illustrating the text even further. For anyone interested cinema’s early history, “How To Film Moving Pictures in the 1910s” is most highly recommended.

The book is available here.

Comments